Do you think that...

The scientific view of life is that it has no intrinsic purpose?

The principles that apply to natural phenomena have nothing to do with those that apply to human cognition and culture?

Recent findings in complexity theory, systems theory, and evolutionary biology tell us otherwise. They point us to profound new insights:

Life has a deep, inner purpose

A purpose that we, as part of life, share

The principles that apply to the natural world reveal deep truths about ourselves—and our society

EXPAND EACH CHAPTER TO READ MORE

Chapter 6. the deep purpose of life

Aristotle was just a teenager when he arrived in Athens from Macedonia to begin his studies at Plato’s famed Academy. For twenty years, he absorbed everything his teacher had to impart. But much of it didn’t make sense to him. Plato taught that the soul was separate from the body, but Aristotle didn’t see how something could exist without a material basis. Plato taught that the tangible world was just a pale imitation of an ideal version in an eternal dimension; to Aristotle, living beings seemed to act according to their own true nature rather than mimic some external ideal.

After Plato’s death, Aristotle set up a competing school in Athens, the Lyceum, where he taught his own philosophy based on his view that every living being has an intrinsic purpose, the expression of its defining essence, which he viewed as its soul. “If the eye were an animal,” he explained, “sight would be its soul, since this is the defining essence of an eye.” Everything an organism did, he believed, was done for the sake of its innate purpose. Things in nature didn’t just happen; they happened for a reason. Plants send their roots into the ground for the sake of nourishment; birds build nests to look after their young; spiders weave webs to catch food. The same was true, he believed, for the way seeds or embryos develop. You can only understand the changes taking place in an acorn, or an egg, if you know its ultimate purpose.

If Aristotle could have explained his ideas to other indigenous cultures around the world, it’s likely they would have been receptive. Virtually all cultures at that time shared an understanding that a life force existed in every living entity, a spirit that impelled them to do what they did. Before hunting an animal or harvesting fruit from a grove, many Indigenous peoples would ritually honor the spirit of the entity from which they took their sustenance.

After Plato’s death, Aristotle set up a competing school in Athens, the Lyceum, where he taught his own philosophy based on his view that every living being has an intrinsic purpose, the expression of its defining essence, which he viewed as its soul. “If the eye were an animal,” he explained, “sight would be its soul, since this is the defining essence of an eye.” Everything an organism did, he believed, was done for the sake of its innate purpose. Things in nature didn’t just happen; they happened for a reason. Plants send their roots into the ground for the sake of nourishment; birds build nests to look after their young; spiders weave webs to catch food. The same was true, he believed, for the way seeds or embryos develop. You can only understand the changes taking place in an acorn, or an egg, if you know its ultimate purpose.

If Aristotle could have explained his ideas to other indigenous cultures around the world, it’s likely they would have been receptive. Virtually all cultures at that time shared an understanding that a life force existed in every living entity, a spirit that impelled them to do what they did. Before hunting an animal or harvesting fruit from a grove, many Indigenous peoples would ritually honor the spirit of the entity from which they took their sustenance.

|

In ancient China, sages developed these indigenous insights into a categorization of the kinds of qi (energy/matter) that existed in an organism. One kind was shen, the vital spirit that animated a living organism. Another was jing, the generative principle that was believed to emerge in an embryo at the moment of conception, driving its growth and eventual reproductive energy. We’ll never know exactly how early Chinese scholars would have interpreted Aristotle’s theories in terms of shen and jing, but it’s likely that his ideas would have made sense to them.

|

This was not the case, however, for European thinkers in the wake of the Scientific Revolution. As we’ve seen, prominent thinkers such as Descartes and Hobbes laid the foundation for the mechanistic worldview that has since become ubiquitous in mainstream thought. If an animal were merely a machine, then by definition it couldn’t have its own intrinsic purpose any more than it could have its own feelings. In the seventeenth century, those scientific pioneers still lived under a Christian worldview, so it was easy enough to attribute the seemingly purposeful activity of nature to a Creator, who instilled purpose in a creature just like a clockmaker instils the purpose of timekeeping into a clock.

By the nineteenth century, when scientists were less willing to resort to theology for ultimate explanations, the problem resurfaced: How could you explain the obviously purposive behavior of living organisms? Some scientists theorized that creatures contained a life-force, an élan vital, that worked according to specific laws, like gravity or electricity. However, by the early twentieth-century, this idea, known as vitalism, fell into such disrepute in mainstream science that it became an object of ridicule. Along with vitalism, any theory that living entities possessed intrinsic purpose—known as teleology—was discarded by mainstream science into the same pit of disdain that contained other heretical ideas we’ve already come across, such as Lamarckian evolution, animal emotions, or plant intelligence—each of which has now been scientifically validated.

For reductionist scientists, the primary challenge in refuting teleology was that living organisms so obviously demonstrate it in everything they do. When a spider tries valiantly to climb out of the bathtub, or when your dog paws at the door because she needs to relieve herself, it’s only too clear they’re acting with purpose. However, with the widespread acceptance of the Modern Synthesis in the mid-twentieth century, biologists declared this challenge resolved. Everything could now be explained by natural selection operating on genes. According to prominent biologist, Ernst Mayr, organisms only seem to behave according to teleology, but their behavior really “owes its goal-directedness to the operation of a program . . . that contains not only the blueprint of the goal but also the instructions of how to use the information of the blueprint.”

However, as we’ve seen, the mechanistic metaphor for life is fundamentally flawed. Life didn’t emerge according to blueprints, and doesn’t operate like a computer program. What does that mean for teleology? Could Aristotle have been right? If life’s purposive behavior is not the result of a program, what really causes it? In this chapter, we’ll discover how, not only does life have purpose, but intrinsic purpose is, in fact, a defining characteristic of life. Research in the dynamics of self-organization is forcing leading scientists to rethink how evolution itself works, and suggests a directionality to life on Earth that requires us to reconsider humanity’s true place within it.

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 6. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth

By the nineteenth century, when scientists were less willing to resort to theology for ultimate explanations, the problem resurfaced: How could you explain the obviously purposive behavior of living organisms? Some scientists theorized that creatures contained a life-force, an élan vital, that worked according to specific laws, like gravity or electricity. However, by the early twentieth-century, this idea, known as vitalism, fell into such disrepute in mainstream science that it became an object of ridicule. Along with vitalism, any theory that living entities possessed intrinsic purpose—known as teleology—was discarded by mainstream science into the same pit of disdain that contained other heretical ideas we’ve already come across, such as Lamarckian evolution, animal emotions, or plant intelligence—each of which has now been scientifically validated.

For reductionist scientists, the primary challenge in refuting teleology was that living organisms so obviously demonstrate it in everything they do. When a spider tries valiantly to climb out of the bathtub, or when your dog paws at the door because she needs to relieve herself, it’s only too clear they’re acting with purpose. However, with the widespread acceptance of the Modern Synthesis in the mid-twentieth century, biologists declared this challenge resolved. Everything could now be explained by natural selection operating on genes. According to prominent biologist, Ernst Mayr, organisms only seem to behave according to teleology, but their behavior really “owes its goal-directedness to the operation of a program . . . that contains not only the blueprint of the goal but also the instructions of how to use the information of the blueprint.”

However, as we’ve seen, the mechanistic metaphor for life is fundamentally flawed. Life didn’t emerge according to blueprints, and doesn’t operate like a computer program. What does that mean for teleology? Could Aristotle have been right? If life’s purposive behavior is not the result of a program, what really causes it? In this chapter, we’ll discover how, not only does life have purpose, but intrinsic purpose is, in fact, a defining characteristic of life. Research in the dynamics of self-organization is forcing leading scientists to rethink how evolution itself works, and suggests a directionality to life on Earth that requires us to reconsider humanity’s true place within it.

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 6. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth

Chapter 7. the tao in my own nature

Blind and deaf from infancy, Helen Keller spent her early childhood “at sea, in a dense fog,” as she later described it. By the age of seven, her only friend, the daughter of her family’s cook, had helped her develop a set of about sixty gestures she used to communicate her basic needs. But she had no clue of what language was, and virtually no conception of the world outside her sensory orbit. A new instructor, Anne Sullivan, tried spelling words out on Helen’s hand, but since Helen had no idea what she was doing, this just got her frustrated. Then, one day, everything changed. While Helen was washing in the morning, Mrs. Sullivan spelled out the word “w-a-t-e-r” in her other hand. Later that day, while filling her mug with water, she spelled the word out again for Helen. In Mrs. Sullivan’s words:

"She dropped the mug and stood as one transfixed. A new light came into her face. She spelled ‘water’ several times. Then she dropped on the ground and asked for its name and pointed to the pump and the trellis and suddenly turning round she asked for my name. I spelled ‘teacher.’ All the way she was highly excited, and learned the name of every object she touched, so that in a few hours she had added thirty new words to her vocabulary. The next morning, she got up like a radiant fairy. She has flitted from object to object, asking the name of everything and kissing me for very gladness . . . Everything must have a name now."

Not only had Helen discovered language, in a flash of inspiration her mind had opened up to an entire universe of possibility. Her face grew more expressive every day. In Helen’s autobiography, she writes: “The living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, set it free!” Helen went on to become a prolific author, lecturer, and an activist for women’s suffrage and other progressive causes.

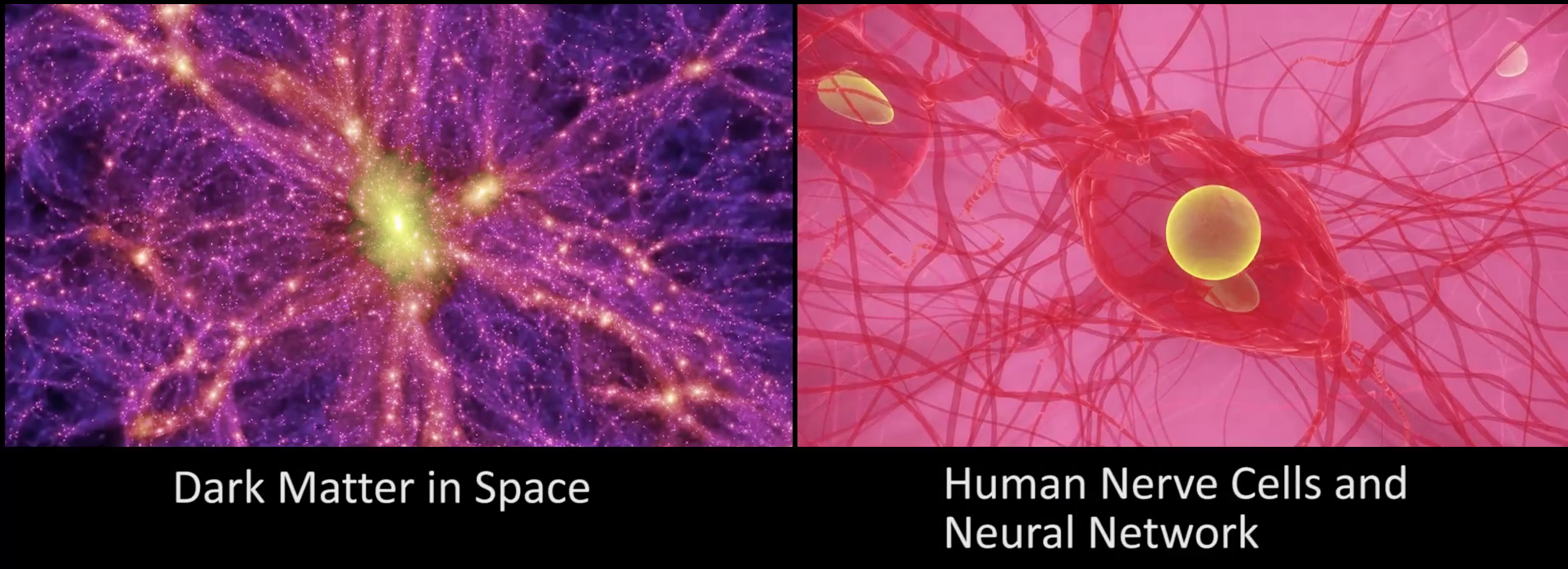

What happened in Helen’s mind at that wondrous moment? We’ve come across other examples of dramatic phase transitions in nature, when different parts of a system coalesce to emerge into a new coherence that couldn’t previously have been imagined. As we’ve seen, the most glorious instance of emergence is life itself, which self-generated billions of years ago, and has never looked back. The shining example of Helen Keller prompts a larger question: can we apply the principles of self-organization to our own human consciousness? If so, what would they tell us about ourselves?

"She dropped the mug and stood as one transfixed. A new light came into her face. She spelled ‘water’ several times. Then she dropped on the ground and asked for its name and pointed to the pump and the trellis and suddenly turning round she asked for my name. I spelled ‘teacher.’ All the way she was highly excited, and learned the name of every object she touched, so that in a few hours she had added thirty new words to her vocabulary. The next morning, she got up like a radiant fairy. She has flitted from object to object, asking the name of everything and kissing me for very gladness . . . Everything must have a name now."

Not only had Helen discovered language, in a flash of inspiration her mind had opened up to an entire universe of possibility. Her face grew more expressive every day. In Helen’s autobiography, she writes: “The living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, set it free!” Helen went on to become a prolific author, lecturer, and an activist for women’s suffrage and other progressive causes.

What happened in Helen’s mind at that wondrous moment? We’ve come across other examples of dramatic phase transitions in nature, when different parts of a system coalesce to emerge into a new coherence that couldn’t previously have been imagined. As we’ve seen, the most glorious instance of emergence is life itself, which self-generated billions of years ago, and has never looked back. The shining example of Helen Keller prompts a larger question: can we apply the principles of self-organization to our own human consciousness? If so, what would they tell us about ourselves?

While this is a relatively new question for modern scientists to ask, it’s one that was self-evident to the Neo-Confucian philosophers who, a thousand years ago, recognized the patterns of the universe—the li—as the principle that connects all things. “There is li in everything, and one must investigate li to the utmost,” proclaimed one sage. This applied as much to one’s own mind as everything else in the physical world. In fact, some Neo-Confucians made no distinction. “The universe is my mind, and my mind is the universe,” stated one. When their greatest philosopher, Zhu Xi, kicked off his program of gewu—the investigation of things—he did so with this intriguing declaration: “If one wishes to know the reality of Tao, one must seek it in one’s own nature."

We’re going to follow the guidance of those Neo-Confucian sages in this chapter, and explore the correspondences between the principles of the Tao and those of human consciousness. The full scope of the Tao is as vast and mysterious as the universe itself, but progress made by modern scientists in identifying key principles of self-organization in nature offers a window into some of those mysteries that would otherwise remain obscure. As Helen Keller’s example suggests, the parallels are striking. We’ll find that studying consciousness as the outcome of the same self-organized processes as the rest of nature overturns some of the cherished beliefs of mainstream theorists. The implications of this approach lead to insights, not just into ourselves, but into the guiding principles of human culture, along with hints about what may be in store for our civilization.

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 5. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth

We’re going to follow the guidance of those Neo-Confucian sages in this chapter, and explore the correspondences between the principles of the Tao and those of human consciousness. The full scope of the Tao is as vast and mysterious as the universe itself, but progress made by modern scientists in identifying key principles of self-organization in nature offers a window into some of those mysteries that would otherwise remain obscure. As Helen Keller’s example suggests, the parallels are striking. We’ll find that studying consciousness as the outcome of the same self-organized processes as the rest of nature overturns some of the cherished beliefs of mainstream theorists. The implications of this approach lead to insights, not just into ourselves, but into the guiding principles of human culture, along with hints about what may be in store for our civilization.

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 5. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth