Scientific reductionists claim the universe is utterly meaningless

Mainstream religious dogma points to another dimension for the source of meaning

What if neither of these propositions is true?

What if meaning itself arises from our interrelatedness?

Modern research in systems theory and cognitive science hints at a profound realization that wisdom traditions around the world have intimated for millennia:

We enact meaning into the universe through how we attune to it

Meaning is a function of connectedness

Once we recognize our part in the web of meaning, we are called to devote ourselves to the flourishing of all life within it

EXPAND EACH CHAPTER TO READ MORE

Chapter 11. everything is connected

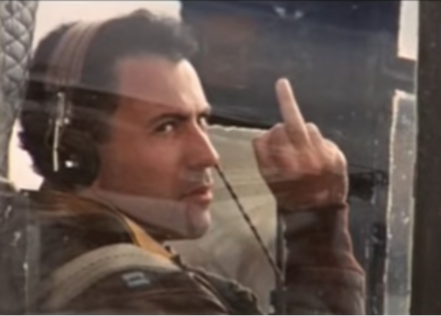

Yossarian—the antihero in Joseph Heller’s Catch-22—doesn’t want to fly any more missions. It’s late in the Second World War and beginning to look like the Allies will be victorious. Yossarian’s squadron flies regular bombing sorties over Italy, but he tells his commanding officer he’s not flying any more, for the simple reason that he doesn’t want to get killed by enemy aircraft fire. “Would you like to see our country lose?” asks his officer. “We won’t lose,” Yossarian answers:

|

"We’ve got more men, more money and more material. There are ten million men in uniform who could replace me. Some people are getting killed and a lot more are making money and having fun. Let somebody else get killed.” “But suppose everybody on our side felt that way.” “Then I’d certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way. Wouldn’t I?” |

When I first read this riposte, as a young student rebelling against established bastions of authority, Yossarian’s logical ruse felt like a liberation— a stand for individual authenticity against a blind herd mentality.

As the years passed, and I became embedded in the free-market capitalist mindset, I would keep referring back to this twisted argument as a refreshing rebuttal of pious morality. If everyone was acting cynically and manipulating the system to get ahead of the pack, then “I’d be a damned fool” to act in any other way, wouldn’t I? It seemed so liberating. It was many years before I began to realize how its apparent emancipatory quality was in reality merely a glib expression of an underlying ethos that venerated the individual above all else—a rallying cry for the “Me Generation,” many of whom became the beneficiaries and cheerleaders of the neoliberal cult of the individual that predominates in our global culture today.

If everyone had followed Yossarian’s logic, of course, Hitler and his Nazi ideology would have won the Second World War. Today, as the world faces the existential threat of climate breakdown, our national leaders act according to a similar twisted logic, making speeches about the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, while privately choosing not to be the “damned fool” acting for the common good while other countries avoid making the tough choices required.

For me, this dog-eat-dog ethic of cynicism reached its nadir during my days as an executive in a credit card company. One day, my boss arrived late for a meeting. He’d been delayed, he explained, by a plumber who, he believed, was overcharging him for some major repair work. “But then again,” he reflected aloud with a self-satisfied smirk, “we’re overcharging him and others like him with our credit card fees. We’re all ripping each other off. In the end, that’s how the world works, isn’t it?”

It may not be how the world works, but it certainly is, to a large extent, how our global economic system works, based on the myth that the most effective way to run a society is for each person to act according to their own self-interest. This individual-oriented ethos has deep roots in our culture, deeper even than capitalism itself. Its origins are to be found in the very idea of an individual as an autonomous agent utterly distinct from the rest of humanity. The concept of the self-contained individual pervades our modern way of thinking so extensively that it seems axiomatic, but it is in fact a construction of the European tradition. Our culture, as we’ve seen, holds a deep-seated belief that an individual’s essence exists in one’s conceptual consciousness, based on the Cartesian dictum: “I think, therefore I am.” Descartes, in turn, inherited from traditional Christianity the idea of the soul as the indestructible core of the individual—one that would end up in either heaven or hell for eternity depending on how God judged it when a person died.

Nowadays, many people no longer believe in a literal heaven and hell, but for over a millennium this was the foundational myth of virtually everyone’s belief system, whether they were simple peasants or learned intellectuals. Now, think about its implications. The underlying premise is that you should be concerned only about your own soul’s welfare. If you end up in heaven, then you’ve got yours—and don’t even think about what happens to anyone else’s soul. To hell with them (quite literally). Occasionally, theologians would speculate on how someone who made it to heaven could remain beatific if they knew a loved one was suffering eternal torment in hell. One theory was that God wiped your mind clean of memories of any loved ones now enduring perpetual torture. Other prominent theologians, amazingly, suggested that those in heavenly bliss would simply rejoice when they heard the “dolorous shrieks and cries” of the damned, knowing that they got their just deserts. Today, while few people focus on an afterlife, the divisions of society have become such that—from a material perspective, at least—heaven and hell are a function of economic disparity. Based on this ingrained cultural baggage of the individual soul, is it any wonder that the wealthy elite feel entitled to enjoy their worldly paradise while billions of other human souls suffer in dire poverty?

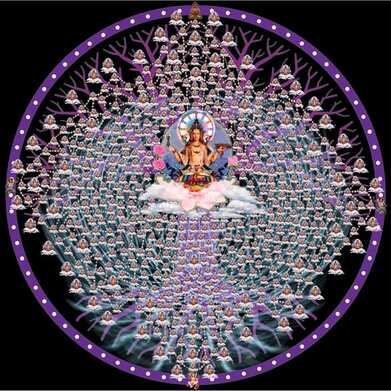

There is a fascinating contrast to the Christian story of the soul’s salvation in the Buddhist conception of the bodhisattva. A bodhisattva, as discussed earlier, is someone who, having worked tirelessly to achieve enlightenment, has arrived at the threshold of nirvana—the opportunity to be released from persistent cycles of reincarnation. But rather than opting for liberation, the bodhisattva chooses to return to the world and work ceaselessly until all beings have awakened from needless suffering. This seems at first like an act of boundless altruism. However, a deeper analysis reveals something even more profound. The bodhisattva has achieved the realization that the boundaries separating the self from others are all mere constructions of a conditioned mind. In this “perfection of wisdom,” the bodhisattva recognizes her inherent interdependence with all sentient beings. It’s not that she is sacrificing herself for the benefit of others—she has awakened to the realization that the very notion of a separate self is a falsehood.

|

A breathtaking Buddhist conception, called the Jewel Net of Indra, memorably captures this idea of deep interconnectedness. In the heavenly abode of the god Indra, there exists a wonderful net that stretches out infinitely in all directions. In every eye of the net, there hangs a glittering jewel. Since the net is infinite, there are an infinite number of jewels. The jewels are polished so perfectly that, if you inspect any one jewel, you discover that all the other jewels, infinite in number, are reflected in it. Moreover, each of the reflections is also reflecting all the other jewels, so the reflecting process itself contains infinite dimensions. |

This image was used by early Buddhist scholars in China to exemplify how, ultimately, our cosmos is one of infinitely repeating interrelationships. These scholars were among the first to use the term li as the principle of connectivity, which Neo-Confucian philosophers later developed into the sophisticated cosmology of li and qi. Connectivity has, of course, been a central theme of this book. We’ve seen how, oftentimes, the way in which things are connected tells us more than the things themselves—in fact, for crucial phenomena such as life, evolution, mind, consciousness, or flourishing, just like Indra’s Net, the more we inspect them, the more we find their very existence is the emergent product of their interconnections.[i]

While Buddhist and Neo-Confucian sages contribute some of humanity’s greatest insights into interconnectedness, they are by no means alone. We’ve seen that Indigenous communities worldwide view relatedness to each other and the natural world as the foundation of identity and well-being. As First Nations scholar Richard Atleo explains, the indigenous principle of tsawalk (meaning “one”) holds that all issues, whether social, political, economic, or philosophical, “can be addressed under the single theme of interrelationships, across all dimensions of reality—the material and the invisible.” And we’ve seen how findings of modern science have arrived at a similar view of the primacy of interconnectedness in understanding our reality.

And yet . . . do you remember Uncle Bob from the Introduction? Steeped in our mainstream culture’s story of separation, Uncle Bob is a hard nut to crack. Perhaps, by this time, having read the book so far, Uncle Bob has let go of the “selfish gene” myth and recognized that life evolved its magnificence through evolutionary leaps of cooperation. Perhaps Uncle Bob has accepted that conceptual consciousness is not his sole seat of identity; that nature has its own intelligence; that animate intelligence connects him to the rest of nature; that nonlinear, self-organized patterns of organization account for the world’s complexity; that his consciousness results from the dynamic integration of neural attractors; that his own well-being requires a healthy society; and that human flourishing itself depends on a healthy Earth. Uncle Bob has come a long way since the beginning of the book. But now, he pauses for a moment, turns and says: “Okay, I grant you all that. But let’s face it. The fact remains that it’s a rat race out there. Everyone is out for themselves, and the system rewards those who are most self-centered. Maybe underneath it all, we are all connected. But in the end, if everyone else is just looking out for themselves and trying to get ahead, then I’d be a damned fool to do otherwise. Wouldn’t I?”

What do we say to Uncle Bob at this point? This chapter can be regarded as a deep inquiry into the question he raises. To confront it fully, we need to dig even further than we’ve gone. Ultimately, Uncle Bob won’t be moved until he’s face-to-face with whatever is most meaningful to him, lurking in the inner core of his being. We must excavate down to the very root of existence, and explore the question of where meaning itself arises. Is Yossarian right that ultimately he needs to look out for “number one,” and the Jewel Net of Indra is nothing more than a lovely fantasy? If we are, in fact, all interconnected, what does that ultimately mean for our lives? How might that affect our own sense of meaning and purpose?

As we embark into these deep underpinnings of reality, is it possible we might come across something that causes even Uncle Bob to see his life from a somewhat different perspective?

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 11. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth

While Buddhist and Neo-Confucian sages contribute some of humanity’s greatest insights into interconnectedness, they are by no means alone. We’ve seen that Indigenous communities worldwide view relatedness to each other and the natural world as the foundation of identity and well-being. As First Nations scholar Richard Atleo explains, the indigenous principle of tsawalk (meaning “one”) holds that all issues, whether social, political, economic, or philosophical, “can be addressed under the single theme of interrelationships, across all dimensions of reality—the material and the invisible.” And we’ve seen how findings of modern science have arrived at a similar view of the primacy of interconnectedness in understanding our reality.

And yet . . . do you remember Uncle Bob from the Introduction? Steeped in our mainstream culture’s story of separation, Uncle Bob is a hard nut to crack. Perhaps, by this time, having read the book so far, Uncle Bob has let go of the “selfish gene” myth and recognized that life evolved its magnificence through evolutionary leaps of cooperation. Perhaps Uncle Bob has accepted that conceptual consciousness is not his sole seat of identity; that nature has its own intelligence; that animate intelligence connects him to the rest of nature; that nonlinear, self-organized patterns of organization account for the world’s complexity; that his consciousness results from the dynamic integration of neural attractors; that his own well-being requires a healthy society; and that human flourishing itself depends on a healthy Earth. Uncle Bob has come a long way since the beginning of the book. But now, he pauses for a moment, turns and says: “Okay, I grant you all that. But let’s face it. The fact remains that it’s a rat race out there. Everyone is out for themselves, and the system rewards those who are most self-centered. Maybe underneath it all, we are all connected. But in the end, if everyone else is just looking out for themselves and trying to get ahead, then I’d be a damned fool to do otherwise. Wouldn’t I?”

What do we say to Uncle Bob at this point? This chapter can be regarded as a deep inquiry into the question he raises. To confront it fully, we need to dig even further than we’ve gone. Ultimately, Uncle Bob won’t be moved until he’s face-to-face with whatever is most meaningful to him, lurking in the inner core of his being. We must excavate down to the very root of existence, and explore the question of where meaning itself arises. Is Yossarian right that ultimately he needs to look out for “number one,” and the Jewel Net of Indra is nothing more than a lovely fantasy? If we are, in fact, all interconnected, what does that ultimately mean for our lives? How might that affect our own sense of meaning and purpose?

As we embark into these deep underpinnings of reality, is it possible we might come across something that causes even Uncle Bob to see his life from a somewhat different perspective?

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 11. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth

Chapter 12. from fixed self to infinite li: the fractal nature of identity

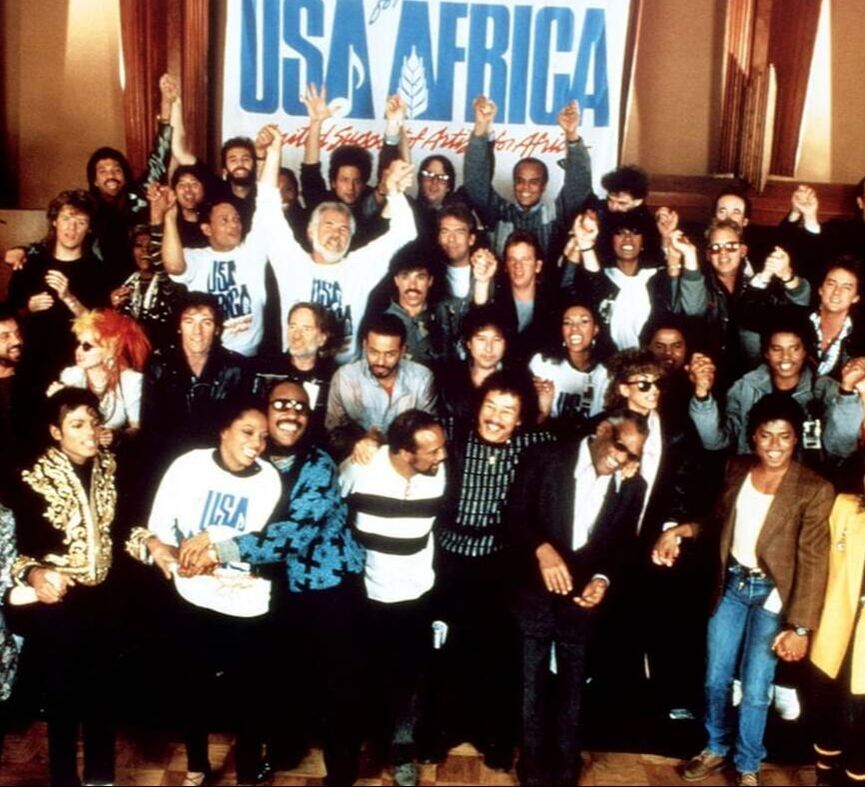

The year 1985 doesn’t stand out as one of history’s most memorable. It followed 1984—the iconic year that gave the title to George Orwell’s classic. The neoliberal takeover of global politics was in full swing, with Ronald Reagan sworn in for his second term, and the historic coalminers’ strike in the UK finally crushed by Margaret Thatcher’s dogged intransigence. Coca-Cola introduced New Coke in one of history’s great marketing blunders, and Greenpeace’s ship Rainbow Warrior was sunk in New Zealand by French agents. But by a strange coincidence of timing, two popular songs topped the charts that spring, both of which chipped away at the dominant worldview portraying individuals as fixed, standalone entities trying to maximize their fortunes in a coldhearted universe.

|

The first of these was a charity single dreamed up by activist performer Harry Belafonte in response to a devastating famine in Ethiopia. Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, and dozens of musical superstars recorded “We Are the World”—a popular anthem of shared global identity with lyrics proclaiming: “We are the world, we are the children . . . let us realize that a change can only come when we stand together as one.” The song was one of the greatest hits of all time, and exceeded the organizers’ hopes, raising over $50 million for humanitarian aid. It’s been appropriately criticized for merely providing a cheap way for people in wealthy countries to absolve themselves of guilt while benefiting from structural global inequalities that remain unresolved. But from a larger historical perspective, it may come to be seen as an early point of light in an awakening global consciousness of shared human identity.

|

|

The other song was less iconic, but also hit a nerve in popular consciousness by offering an alternative take on the true meaning of identity. In “Highwayman,” recorded by the country music supergroup of Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and Kris Kristofferson, each singer takes turns to chronicle a kind of cosmic autobiography of a spirit reincarnated in various bodies over the ages. “I was a highwayman,” intones Nelson. “The bastards hung me in the spring of twenty-five, But I am still alive.” Kristofferson was a sailor: “They said that I got killed, But I am living still.” Jennings was a dam builder who slipped to his death “but I am still around.” Finally, Johnny Cash prophecies that “I’ll fly a starship across the universe divide,” finishing:

|

And when I reach the other side

I'll find a place to rest my spirit if I can

Perhaps I may become a highwayman again

Or I may simply be a single drop of rain

But I will remain

And I'll be back again, and again and again.

I'll find a place to rest my spirit if I can

Perhaps I may become a highwayman again

Or I may simply be a single drop of rain

But I will remain

And I'll be back again, and again and again.

What’s fascinating about this song, which topped the country charts, was the implicit cosmology it spun, depicting a kind of spirit, characterized by a sense of defiant, rugged adventure, transcending the life and death of any single person.

Part of the song’s appeal is that it hints at a different kind of reality: one where an individual’s life is made meaningful by qualities he or she temporarily embraces as part of a vaster, epic adventure. Similarly, the “feel good” aura generated by “We Are the World” suggests the possibility of a broader identity transcending a bounded self, somehow linking all humanity together in a common bond. Looking back over the decades of neoliberal capitalism since these songs came out, it’s easy to dismiss their intimations as mere poetic flourishes. But as we’ve seen, the current worldview that dominates mainstream thought is deeply flawed. Once we begin to embrace the reality of a connected universe, new forms of identity naturally emerge. In this chapter, we’ll explore some fascinating aspects of the landscape unfurled by a worldview of connectedness. We’ll see how a scientifically rigorous, careful investigation of the nature of existence leads to unexpected outcomes—even to a realization that, rather than mere aspirational sentiments, those hits from 1985 offered glimpses of a more coherent reality than the hard-nosed worldview promulgated today by mainstream discourse.

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 12. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth

Part of the song’s appeal is that it hints at a different kind of reality: one where an individual’s life is made meaningful by qualities he or she temporarily embraces as part of a vaster, epic adventure. Similarly, the “feel good” aura generated by “We Are the World” suggests the possibility of a broader identity transcending a bounded self, somehow linking all humanity together in a common bond. Looking back over the decades of neoliberal capitalism since these songs came out, it’s easy to dismiss their intimations as mere poetic flourishes. But as we’ve seen, the current worldview that dominates mainstream thought is deeply flawed. Once we begin to embrace the reality of a connected universe, new forms of identity naturally emerge. In this chapter, we’ll explore some fascinating aspects of the landscape unfurled by a worldview of connectedness. We’ll see how a scientifically rigorous, careful investigation of the nature of existence leads to unexpected outcomes—even to a realization that, rather than mere aspirational sentiments, those hits from 1985 offered glimpses of a more coherent reality than the hard-nosed worldview promulgated today by mainstream discourse.

Excerpt from The Web of Meaning, Chapter 12. Purchase: USA/Canada | UK/Commonwealth